Women want men, career, money, children, friends, luxury, comfort, independence, freedom, respect, love and cheap stockings that don’t run.

Nylon stockings made their debut in my hometown, Wilmington, Delaware, on October 24, 1939. That’s because Wallace Hume Carothers, the chemist who invented the synthetic material in 1935, worked for the DuPont company, which is headquartered there. In fact, the first test sale to DuPont employees’ wives took place at the company’s experimental station, just up the street from my childhood home. Not long before the 4,000 pairs of stockings sold out—in only three hours!—DuPont had had women modeling nylon hosiery at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, touting nylon as a synthetic fabric made of “carbon, water and air.” A prototype of that initial run (get it?) can be found in the Smithsonian’s collection.

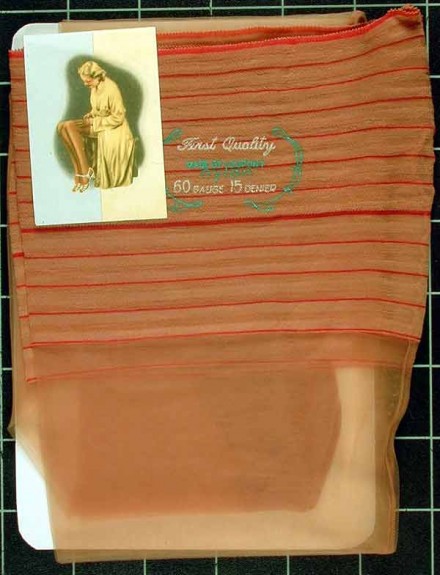

This is the first pair of experimental nylon stockings made by Union Hosiery Company for DuPont in 1937. The leg of the stocking is nylon, the upper welt, toe and heel are silk, and cotton is used in the seam. The nylon section of the stocking would not take the silk dye, and dyed to black instead of brown. (National Museum of American History)

From the moment DuPont realized what kind of stretchy, durable, washable, dryable revolution it had synthesized, the company channeled its invention to women’s hosiery, a huge potential market. Hemlines were rising throughout the 1930s, and stockings, made at that time from silk or rayon, had become an essential component to a woman’s wardrobe, even though they were delicate and prone to runs. (The delicacy didn’t hurt the bottom line; women purchased an average of eight pairs of stockings per year during that decade.) Then came DuPont’s wonder fabric; the word “nylon,” as the lore goes, originated from the attempted coinage “nuron,”—”no run” spelled backward. Trademark issues caused DuPont to adapt the word to “nilon,” and then finally to “nylon” to remove any pronunciation ambiguity.

DuPont’s initial sales success in Wilmington was just the beginning of the nylon stocking craze. On May 16, 1940, officially known as “Nylon Day,” four million pairs of brown nylons landed on department store shelves throughout the United States at about $1.15 per pair. They sold out within two days. Silk stockings—which didn’t stretch, were challenging to clean, and ripped easily, but had been standard—were quickly supplanted.

That is, until the war came around. As quickly as nylon stockings found their way into department stores and boutiques, providing women with inexpensive, longer-lasting hosiery options, they disappeared. After Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941, and the United States entered World War II, the material that had its beginnings briefly as toothbrush bristles (prior to entering the women’s hosiery market) was severely rationed and channeled into war efforts. Nylon was permitted only in the manufacturing of parachutes, tire cords, ropes, aircraft fuel tanks, shoe laces, mosquito netting and hammocks, aiding in the U.S.’s national defense. Because American women had seen the future and it had them wearing nylons, they had to be inventive to meet their leg-beautifying needs (Paint-on stockings, anyone? More on that soon.) or turn to the black market (a “diverted” nylon shipment earned one sly entrepreneur $100,000).

When the war was over and rations were eased, nylon stockings returned to stores and sold quickly. In 1945, “nylon riots” ensued around the country when hundreds, and sometimes even thousands of women, queued up to try to snag a pair. The situation got out of hand in Pittsburgh when 40,000 people lined up for over a mile vying for 13,000 pairs.

Lines formed when nylons were finally available again in autumn 1945 after the end of World War II. (German Hosiery Museum)

But Carothers, nylon’s creator, didn’t get to see the mania around his invention. After great scientific success (he also invented neoprene and the first synthetic musk), he committed suicide in 1936 after battling depression for years. And his death, alongside some bad press from the Washington News claiming that nylon could be made from cadaverine, a substance formed during putrefaction in dead bodies, put a morbid slant on the synthetic material.

Nylon’s bad rep was short-lived. After it was lauded for winning the war and changing the future of American women’s gams, the demand for nylon only continued to increase as DuPont shrewdly promoted the product. In one article, Joseph Lebovsky, a chemical engineer working at DuPont’s nylon lab (and, in keeping with tiny Delaware’s inevitable connections, a good friend of my grandparents), recounted how throughout the 1940s, demand remained so high that no matter how established the company, DuPont “had to make sure customers who wanted nylon had the money to pay [in advance] for it. . . . Even Burlington Mills would send a check for $100,000 to fill an order. . . . Everybody wanted nylon.”

After nylon came other easy-care DuPont synthetics (Dacron, Orlon, Bri-Nylon, Tricel), popularized by the company’s business savvy. The company realized, quite wisely, that to win over the textile market, and consumers in general, it had to appeal to high-end fashion designers, and in particular, Parisian couturiers. With its fabric development department, the company courted designers to produce clothing using its inventions. By 1955, DuPont landed a major victory when 14 synthetic fabrics, including quite a few of DuPont’s, were used in gowns from Coco Chanel and Christian Dior. DuPont even hired fashion photographer Horst P. Horst to document the runway fashions and circulated those images in press releases.

As you might expect, synthetic fabrics were key ingredients in the space age fashion trend, mentioned last week in Threaded. But sartorially speaking, they fizzled out. By the late ’60s, the fabrics disappeared from the runways. But they were embraced by the mainstream, at least for a while. Then their artificial, shiny look began to appear tacky (gotta love a red polyester butterfly-collared shirt…) as people returned to wearing natural fabric.

Today we may see (or feel) less nylon in our clothes, but its presence, mostly in the form of plastic, is established in our kitchens, bathrooms and offices. And while Phyllis Diller’s legacy lives on as nylon remains an essential ingredient for our reasonably priced stockings, tights, and knee-highs today, when it comes to the flesh-toned pantyhose business, it has taken a tumble in the past couple decades as women are more likely to go bare-legged. But I can only hope that DuPont is hard at work creating the next revolutionary material to make them less disposable and more earth-friendly.