On May 1, 1920, the Saturday Evening Post published F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” a short story about a sweet yet socially inept young woman who is tricked by her cousin into allowing a barber to lop off her hair. With her new do, she is castigated by everyone: Boys no longer like her, she’s uninvited to a social gathering in her honor, and it’s feared that her haircut will cause a scandal for her family.

In the beginning of the 20th century, that’s how serious it was to cut off your locks. At that time, long tresses epitomized a pristine kind of femininity exemplified by the Gibson girl. Hair may have been worn up, but it was always, always long.

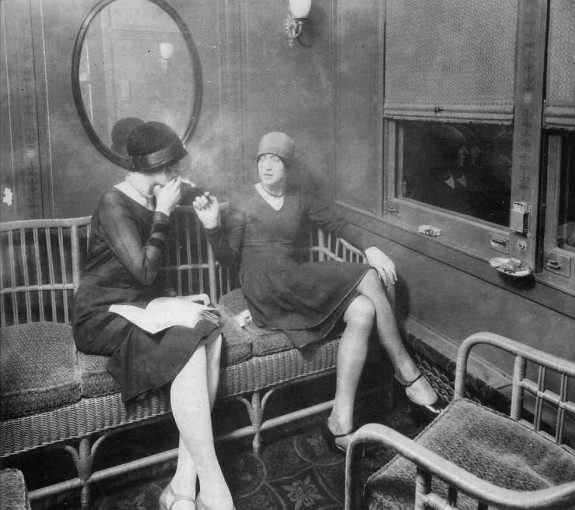

Part and parcel with the rebellious flapper mentality, the decision to cut it all off was a liberating reaction to that stodgier time, a cosmetic shift toward androgyny that helped define an era.

The best-known short haircut style in the 1920s was the bob. It made its first foray into public consciousness in 1915 when the fashion-forward ballroom dancer Irene Castle cut her hair short as a matter of convenience, into what was then referred to as the Castle bob.

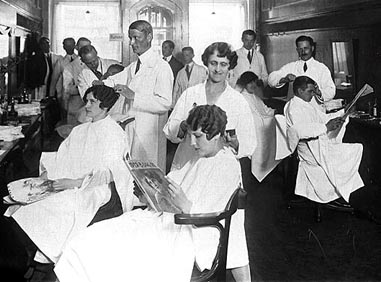

Early on, when women wanted to emulate that look, they couldn’t just walk into a beauty salon and ask the hairdresser to cut off their hair into that blunt, just-below-the-ears style. Many hairdressers flat out refused to perform the shocking and highly controversial request And some didn’t know how to do it since they’d only ever used their shears on long hair. Instead of being deterred, the flapper waved off those rejections and headed to the barbershop for the do. The barbers complied.

A collection of American Hairdresser magazines published in 1920s.

Hairdressers, sensing that the trend was there to stay, finally relented. When they began cutting the cropped style, it was a boon to their industry. A 1925 story from the Washington Post headlined “Economic Effects of Bobbing” describes how bobbed hair did wonders for the beauty industry. In 1920, there were 5,000 hairdressing shops in the United States. At the end of 1924, 21,000 shops had been established—and that didn’t account for barbershops, many of which did “a rushing business with bobbing.”

As the style gained mass appeal—for instance, it was the standard haircut in the widely distributed Sears mail order catalog during the ’20s—more sophisticated variations developed. The finger wave (S-shaped waves made using fingers and a comb), the Marcel (also wavy, using the newly invented hot curling iron), shingle bob (tapered, and exposing the back of the neck) and Eton crop (the shortest of the bobs and popularized by Josephine Baker) added shape to the blunt cut. Be warned: Some new styles weren’t for the faint of heart. A medical condition, the Shingle Headache, was described as a form of neuralgia caused by the sudden removal of hair from the sensitive nape of the neck, or simply getting your hair cut in a shingle bob. (An expansive photograph collection of bob styles can be found here.)

Accessories were designed to complement the bob. The still-popular bobby pin got its name from holding the hairstyle in place. The headband, usually worn over the forehead, added a decorative flourish to the blunt cut. And the cloche, invented by milliner Caroline Reboux in 1908, gained popularity because the close-fitting hat looked so becoming with the style, especially the Eton crop.

Although later co-opted by the mainstream to become status quo (along with makeup, underwear and dress, as earlier Threaded posts described), the bob caused heads to turn (pun!) as flappers turned the sporty, cropped look into another playful, gender-bending signature of the Jazz Age.

Has there been another drastic hairstyle that’s accomplished the same feat? What if the 1990s equivalent of Irene Castle—Sinead O’Connor and her shaved head—had really taken off? Perhaps a buzz cut would have been the late 20th-century version of the bob and we all would have gotten it, at least once.